POKS!

Legendaarisen Led Zeppelin I:n avauskappale Good times bad times on ensimmäinen koskaan äänittämäni/taltioimani biisi. Oli loppukesä 1969, istuin keittiön pöydän ääressä, ketään muita ei ollut kotona sillä hetkellä. Olin vastikään saanut kuukauden palkan kesätöistä ja ostanut sen ajan teknisen uutuuden eli radiokasettimankan, jonka kasettimekaniikka toimi ikäänkuin vaihdekeppisäädöillä. Systeemi oli melko kankea mutta yksinkertainen ja käteväkin, joskin ankarassa tehokäytössä altis kulumaan ja rikkoutumaan.

Seuraavana kesänä [ks.PS.] hankin sitten äänentoistoltaan paljon paremman ja kasetteihin verrattuna äänentaltiointi-kapasiteetiltaan huomattavasti suuremman neliraita-kelamankan. Yhteen kelaan mahtui tuntikaupalla musiikkia Sitäpaitsi äänitin tälle kelamankalle yksittäisten biisien sijasta kokonaisia LP-levyjä [sen suuremman] kyläkaupan poikien upouusista stereolaitteista. Äänitysten laatu oli mielestäni aivan huippuluokkaa verrattuna rämppään kasettiveiviini. Taisin hetkittäin tuntea itseni melkein onnelliseksi.

Led Zeppelinin esikois-LP:n single-biisit Good times bad times ja Communication breakdown ovat kumpikin vahvasti The Who-vaikutteisia. Itse asiassa juuri Whon loistava mutta mieleltään hiukan sekopäinen [luova?] rumpali Keith Moon tavallaan ja tahtomattaan 'melkein' keksi bändin nimen. Tosin Lead Zeppelin tarkoitti hänellä huonoa keikkaa, joka lopulta romahti alas kuin lyijy-zeppeliini. Idea oli kuitenkin valmis ja vain yksi kirjain muutettiin. Tällä tavoin The New Yardbirds oli muuttunut Led Zeppeliniksi eikä edes Zeppelinin perikunta saanut nimen käyttöä kielletyksi.

Jo esikois-LP kokonaisuudessaan sisältää kuitenkin yhtyeen tulevien levyjen teemallisen repertuaarin. Löytyy kerrassaan mahtavaa [ajoittain myös herkkää] hard rock- tai heavy-bluesia, folk-balladinomaisia aineksia - jopa flamenco- ja itämais-tyyppisiä kokeiluja sekä tietysti Jimmy Pagen 'stravinskimaisen' psykedeelisiä kitaravalleja equalisaattorilla, kaiuilla, tremololla ynnä muilla ääniefekteillä saundattuna - [Dazed and confused'n live-versio olisi paras esimerkki Pagen musiikillisesti vaikuttavasta (eikä pelkästään itsetarkoituksellisesta) efekti-äänimaalailusta].

Paitsi mainitut single-biisit myös koko Zeppelin-ykkönen on erittäin merkittävä rock-musiikillisen makuni alkukehityksen kannalta - tutustuinhan Zeppeliiniin aivan samoihin aikoihin kuin Creedenceenkin. Olen toki viimeistään Green riveristä lähtien ollut vannoutunut John Fogerty/CCR- ja ylipäätään rock- sekä rythm&blues-mies, mutta Zeppelin, Cream, Deep Purple, Rolling Stones, Jimi Hendrix, Johnny Winter, Beatles Jethro Tull jne. nousivat tiukasti CCR:n peesiin. Itse asiassa melko suuri osa -60-luvun loppupuolen ja -70-luvun alun todella merkittävistä bändeistä ja kitaristeista on tullut vuosien mittaan käytyä kohtuullisen hyvin läpi - eräät useaan kertaan.

Myös progempi rock - etenkin Procol Harum, Nice, Emerson, Lake&Palmer ja Blood, Sweat&Tears ovat nousseet 'pistepörssissäni' aiempaa korkeammalle - olkoonkin, että kuuntelin niitä[kin] aika paljon jo -70-luvun alussa - [mainittakoon myös Pink Floyd, vaikken siitä pidäkään yhtä paljon kuin edellä mainituista].

Alkuperäistä mustaa bluesia aloin arvostaa ja ymmärtää [Creamistä, Zeppelinistä, Hendrixistä ja Winteristä huolimatta] tosissani vasta joskus -70-luvun puolivälissä [en tosin ole mikään blues-friikki levyjenkeräilijä; ylipäätään en ole ikinä keräillyt säilyttämistarkoituksessa yhtään mitään - en oikeastaan edes kirjoja]. Steve Ray Vaughanin kitara-virtuositeetti nosti sittemmin bluesia kohtaan tuntemani arvostuksen entistä korkeammalle.

Vaikka olenkin populaarimusiikissa pitänyt eniten vanhasta rock&rythm&bluesista, niin [Spinozaa mukaillakseni] ilman muuta kaikki erinomainen tässä maailmassa [genrestä riippumatta] on aina yhtä vaikeaa kuin harvinaistakin. Ei siis pidä hirttää omia makutottumuksiaan vain yhteen tai edes kahteen genreen, sillä kaikista tyylilajeista löytyy omat neronsa, jotka tekevät aivan varmasti positiivisen vaikutuksen kehen tahansa [tai sitten kyseessä täytyy olla asenteiltaan täysin muumioitunut fundamentalisti ellei peräti imbesilli].

*

Mutta tosiaan - minulla on erittäin elävä ja selkeä muistikuva Good times bad times'in kasettiäänityksestä elokuussa -69. Niinkuin myös kuukautta myöhemmin tapahtuneesta CCR:n Green river-LP:n äänityksestä 'vaihdekeppimankalleni'. Seuraavana kesänä alkanut kelanauhurikausi kesti reilut kaksi vuotta, minkä jälkeen sekin mankka [Uher] oli tiensä päässä. En vienyt Uheria korjattavaksi vaan ostin uuden ja parempilaatuisen kasettivermeen, sillä kasetti-aikakausihan oli vasta alkanut.

Hyvät stereolaitteet olivat minulle siihen aikaan liian kalliita eikä niitä sitäpaitsi voinut kuljettaa kätevästi mukana kuten ei isoa kelanauhuriakaan.Tosi laadukkaat ja arvokkaat stereot [Pioneer] ostin vasta 1987 [about 7700 mummon markkaa]. Kaksi vuotta myöhemmin [jälleen kerran Hesaan päin lähtiessäni] annoin ne veljelleni Jarille käytettäväksi ja säilytettäväksi, mutten ole sen koommin pois hakenut. En pidä teknisten vempeleitten paljoudesta. Minun puolestani lähes kaiken informaatio-tekniikan saisi fokusoida tietokoneeseen - ja niin tuleekin käymään, joskaan minä itse en ole sitä enää näkemässä.

PS.

Kesän aikana 1970 rakennuksella urakkaporukan apumiehenä [ja myös urakkakorvaukseen oikeutettuna] sain yhtäkkiä mielestäni uskomattoman hyvää palkkaa [iso ja vahva nuori sälli otettiin kai mieluusti puolijuoppojen kirvesmiesten, raudoittajien ja muurarien juoksutettavaksi], joten ostin kelanauhurin lisäksi kesän aikana myös japanilaisen [hyvin toimivan] kitarakopion puoliakustisesta Rickenbackerista - aivan samanlaisen, jota John Fogerty käytti CCR:ssä [Rickenbacker 325, lyhytkaulainen malli]. Tätä seikkaa en tosin tajunnut kuin vasta myöhemmin.

Joku ketale varasti tuon skitan kolme vuotta myöhemmin alivuokralaiskämpästäni 1973 Kotkan Korkeavuorenkadulla ollessani päävuokralaisen eli S.O:n kanssa viettämässä juhannussekoilua Kotkan Kaunissaaressa [varas oli siististi rikkonut ulko-oven lasi-ikkunan].

Huom! Rotta! Palauta minulle jo viimeinkin se skitta!

Tämän ensimmäisen oman sähkökitaran 'väkivaltainen' menettäminen aiheutti minulle ilmeisesti niin kovan trauman, että sain pakkomielteen ostaa vuosien varrella tilalle uusia kitaroita [joita niitäkin olen sittemmin lahjoitellut veljelleni, joka on sentään ihan oikea muusikko toisin kuin minä, joka soittelen vain omaksi ilokseni].

II

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=A25HC-INCaY

Led Zeppelin - Led Zeppelin [Full Album] - - Huomatkaa siis, että kyseessä on koko albumi. Saas nähdä, koska Zeppelinin tunnetusti niuho copyright-koneisto poistaa tämän uploadin tuubista? Puolisen vuotta se on jo saanut olla näytillä ja kuulolla.

3

The most revolutionary album in hard rock history. And boy, it's awesome!

1. Good Times Bad Times - 0:00

2. Babe I'm Gonna Leave You - 2:46

3. You Shook Me - 9:27

4. Dazed and Confused - 15:56

5. Your Time Is Gonna Come - 22:21

6. Black Mountain Side - 26:36

7. Communication Breakdown - 28:42

8. I Can't Quit You Baby - 31:11

9. How Many More Times - 35:54

Led Zeppelin is the debut album of the English rock band Led Zeppelin. It was recorded in October 1968 at Olympic Studios in London and released on Atlantic Records on 12 January 1969 in the US and 31 March 1969 in the UK. The album featured integral contributions from each of the group's four musicians and established Led Zeppelin's fusion of blues and rock. Led Zeppelin also created a large and devoted following for the band, with their take on the emerging heavy metal sound endearing them to a section of the counterculture on both sides of the Atlantic.

Although the album initially received negative reviews, it was commercially very successful and has now come to be regarded in a much more positive light by critics. In 2003, the album was ranked number 29 on Rolling Stone magazine's list of the 500 greatest albums of all time.

*

http://fi.wikipedia.org/wiki/Led_Zeppelin

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Led_Zeppelin

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Led_Zeppelin_(album)

http://fi.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Yardbirds

Olen perehtynyt melkein kaikkiin asioihin ja ymmärrän niitä, jos vain haluan. Ainoastaan omat tekoni, tunteeni ja naisen logiikka ovat jääneet minulle mysteereiksi.

August 31, 2011

August 30, 2011

Jumala ei ole kuva eikä kaltaisuus [imaginaatio] vaan symbolisen järjestelmän [kielen] mahdoton mahdollisuusehto [reaalinen]

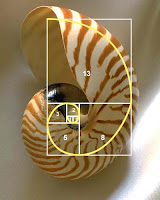

Yläkuva: Fideistin/ateistin 'musta' Jumala on symboli, joka representoi mahdottomuutta [sikäli kuin mahdottomuutta voi representoida]. Loogiselle fideistille Jumala on havainnon ja koetun perimmäinen ehto, joka ei ilmene maailmassa oliona tai ilmiönä. Se voidaan ainoastaan konstituoida maailman mahdollisuusehdoksi kuten tiedostamaton konstituoidaan subjektin mahdollisuusehdoksi.

Keski- ja alakuva: Panteistin Jumala on luonnollinen, havaittu, mitattu ja siten aina positiivisesti määritelty objekti, joka ei representoi mitään vaan ilmenee positiivisena olevana [joka kategorisen virheellisesti samaistetaan olemassaolonsa olemiseksi - ikäänkuin olemassaolo olisi määrällinen ja evolutiivinen suure/määre].

Panteistinen ateisti pitää J/jumalanaan koko luontoa ja/tai koko maailmankaikkeutta sekä sen rakennetta [esim. Fibonaccin numerosarjasta syntyvää muodollista rakennetta/strukturaalista mallia, jota monet luonnon ilmentymät (esim. simpukka) näyttäisivät aktuaalistuessaan ikäänkuin imitoivan].

Looginen fideisti/ateisti sen sijaan ymmärtää Jumalan olevan ei-mitään eli olioitten, ilmiöitten ja rakenteitten mahdollisuusehto - se, mikä tekee maailman olioitten ja ilmiöitten olemassaolon/olemisen mahdolliseksi, mutta joka/mikä ei itse voi tällaisen maailman mahdollisuusehtona olla sen mahdollinen olio.

1

Tämä päre on kommentti nimimerkki Valkean kommenttiin päreessäni 'Äärellisyys ei ole asia, joka estää meitä ratkaisemasta mysteeriä, vaan se on mysteeri itse'.

*

Toistetaan ja tarkennetaan - vielä kerran. Sinä olet panteisti [et ainakaan näytä ymmärtäneen perimmäistä pointtiani]. Minä sen sijaan olen fideisti/ateisti.

Ihmisellä ei voi olla mitään positiivista tietoa Jumalasta, koska Jumala on tietämisemme mahdollisuuden perimmäinen ehto eikä siis voi kuulua havaittavana eli positiivisesti siihen maailmaan, jonka ehto se on.

Tässä merkityksessä ja mielessä Jumala on mahdoton [Jean-Luc Marion, Tuomas Nevanlinna].

Samassa mielessä eli analogisesti tietoisuus ei ole jotain, joka voidaan tietää vaan jotain, joka tietää. Samassa mielessä silmä, joka näkee maailman, ei voi nähdä itseään.

Minä puhun Jumalasta olemisena eli olemassaolon perustana, sinä sen sijaan pidät J/jumalaa olevana oliona tai rakenteena, eivätkä nämä kaksi ontologista kategoriaa palaudu kausaalisesti toisiinsa, koska ensimainittu on transsendentaalinen kategoria ja jälkimmäinen empiiris-historiallis-määrällisen kehityksen summa. - - Ikäänkuin olemassaolon perusta löytyisi materiaalisesta evoluutiosta - ikäänkuin olemassaolo/oleminen kehittyisi asteittain fysiikan ja evoluution lakien eli luonnonvalinnan vaikutuksen materiaalisena 'sopeutumana' siinä missä kaikki muutkin materiaaliset oliot - [jos en ole teisti en ole myöskään uskonnollinen panenteisti].

Oleminen [a fortiori: olemassaoleva oleminen eli Jumala] on olevan perimmäinen syy, jota ei voi johtaa mistään - muutenhan se ei olisi syy vaan seuraus jostain itseään ontologisesti perustavammasta.

Tällainen perusta tai ehto ajattelun mahdollisuudelle on episteemistä muttei ontologista antirealismia. Jos et ymmärtänyt tai olet eri mieltä, voidaan lopettaa tähän, koska emme puhu samasta asiasta eikä intuitiivisia käsityksiämme järjenkäytön tavasta ja mahdollisuusehdoista voi mitenkään sovittaa yhteen.

Sinä elät imaginaarisessa maailmassa, sillä se, joka luulee kykenevänsä kuvaamaan Jumalaa 'oikein', on langennut imaginaarisen interpellaation ansaan fantisoimalla, että Jumala olisi jotain hänen itsensä kaltaista, koska täydellistä toiseutta [reaalinen] on mahdoton kuvitella ilman samaistumista/identifikaatiota [ikäänkuin omana kuvana] tai tietää muuten kuin symbolisena fiktiona [Jumala Sanana ja Lakina].

Niinpä imaginaarinen usko jos mikä on antropomorfismia ja projektiota, koska se tekee Jumalasta oman kuvansa [jumalanpilkkaa siis!].

Symbolinen [fiktiivinen] usko, jota fideismi tai ateismi [uskon kielto] edustavat sen sijaan tunnustaa tiedon [ja siten myös uskon] mahdollisuuden rajat eikä suostu puhumaan [tai ainakin varoo puhumasta] sellaisesta, josta ei mitään voi tietää.

Toki jokainen saa kuvitella niin paljon kuin haluaa, mutta silti uskon ja imaginaation sekoittaminen keskenään on aina sukua animismille ja ylipäätään polyteismille.

Valitan - mutta en voi uskoa niinkuin panteisti ja polyteisti ja nimenomaan sen vuoksi, että haluan uskoa [tai epäuskoa] enkä haaveilla itseidenttisyydestä [joka on harhaa] ja siten kuvitella jonkin käsittämättömän olion [ikäänkuin Jumala olisi olio] kaltaisekseni.

2

Tiedon looginen mahdottomuus Jumalan suhteen voi siis johtaa yhtä hyvin fideismiin kuin ateismiinkin, mutta ei panteismiin ja polyteismiin. Huomautan, ettei tämä päättely ole agnostismia, koska kaikki todennäköiset evidenssit Jumalan olemassaolon puolesta tai sitä vastaan ovat [jopa tieteellistä] imaginaatiota, joka legitimoidaan aina uskona [symbolisen rekisterin] Suureen Toiseen - olipa tuo toinen sitten Jumala [kosmis-moraalisena auktoriteettina] tai Tiede [tieteen 'objektiivisena' asiantuntija-auktoriteettina].

Sanoudun irti tällaisesta uskosta/epäuskosta ja perustelen oman fideismini/ateismini deduktiivisesti negatiivisella [apofatisella] teologialla.

Mystiikka voi olla hyväksyttävää vain apofatisista lähtökohdista. Lukekaa esim. Greorios Nyssalaisen analyysia mystisestä kokemuksesta eli Mooseksesta Siinain vuorella. Lopussa on on aina pimeys, joka muuttuu valoksi - jos on muuttuakseen - - .

Mitään positiivista evidenssiä Jumalasta meille ei kuitenkaan voi olla olemassa. Emme siis myöskään voi tietämällä tietää, oliko Mooses Jumalan kohdatessaan a] mielenhäiriössä, b] keksikö hän tarinan Jumalan kohtaamisesta ja tämän käskyt omasta päästään [siis valehteli Jumalasta puhuessaan] vai c] puhuiko hän niin sanotusti totta/rr.

Onhan tuossa jo kolme vaihtoehtoa - niinkuin pluralistisina aikoina kai olla pitääkin. Nyt eikun suvaitsevaisuutta kehiin ;\].

*

http://actuspurunen.blogspot.com/2011/08/aarellisyys-ei-ole-asia-joka-estaa.html

http://www.cla.purdue.edu/english/theory/psychoanalysis/lacanstructure.html

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jacques_Lacan

http://fi.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fundamentaaliontologia

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pantheism

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fideism

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jean-Luc_Marion

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Panentheism

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Apophatic_theology#In_the_Christian_tradition

http://looneytunes09.wordpress.com/2011/07/29/part-ii-back-in-time-brings-blackness/

http://www.shaeqkhan.com/2010/03/20/the-fibonacci-obsession/

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fibonacci_number

http://mathforum.org/mathimages/index.php/Fibonacci_Numbers

http://taicarmen.wordpress.com/2011/03/08/the-connectivity-of-form-finding-meaning-in-the-golden-mean/

http://www.tiede.fi/keskustelut/biologia-ja-ymparisto-f9/pyha-geometria-fibonacci-ja-phi-t36007-15.html

Keski- ja alakuva: Panteistin Jumala on luonnollinen, havaittu, mitattu ja siten aina positiivisesti määritelty objekti, joka ei representoi mitään vaan ilmenee positiivisena olevana [joka kategorisen virheellisesti samaistetaan olemassaolonsa olemiseksi - ikäänkuin olemassaolo olisi määrällinen ja evolutiivinen suure/määre].

Panteistinen ateisti pitää J/jumalanaan koko luontoa ja/tai koko maailmankaikkeutta sekä sen rakennetta [esim. Fibonaccin numerosarjasta syntyvää muodollista rakennetta/strukturaalista mallia, jota monet luonnon ilmentymät (esim. simpukka) näyttäisivät aktuaalistuessaan ikäänkuin imitoivan].

Looginen fideisti/ateisti sen sijaan ymmärtää Jumalan olevan ei-mitään eli olioitten, ilmiöitten ja rakenteitten mahdollisuusehto - se, mikä tekee maailman olioitten ja ilmiöitten olemassaolon/olemisen mahdolliseksi, mutta joka/mikä ei itse voi tällaisen maailman mahdollisuusehtona olla sen mahdollinen olio.

1

Tämä päre on kommentti nimimerkki Valkean kommenttiin päreessäni 'Äärellisyys ei ole asia, joka estää meitä ratkaisemasta mysteeriä, vaan se on mysteeri itse'.

*

Toistetaan ja tarkennetaan - vielä kerran. Sinä olet panteisti [et ainakaan näytä ymmärtäneen perimmäistä pointtiani]. Minä sen sijaan olen fideisti/ateisti.

Ihmisellä ei voi olla mitään positiivista tietoa Jumalasta, koska Jumala on tietämisemme mahdollisuuden perimmäinen ehto eikä siis voi kuulua havaittavana eli positiivisesti siihen maailmaan, jonka ehto se on.

Tässä merkityksessä ja mielessä Jumala on mahdoton [Jean-Luc Marion, Tuomas Nevanlinna].

Samassa mielessä eli analogisesti tietoisuus ei ole jotain, joka voidaan tietää vaan jotain, joka tietää. Samassa mielessä silmä, joka näkee maailman, ei voi nähdä itseään.

Minä puhun Jumalasta olemisena eli olemassaolon perustana, sinä sen sijaan pidät J/jumalaa olevana oliona tai rakenteena, eivätkä nämä kaksi ontologista kategoriaa palaudu kausaalisesti toisiinsa, koska ensimainittu on transsendentaalinen kategoria ja jälkimmäinen empiiris-historiallis-määrällisen kehityksen summa. - - Ikäänkuin olemassaolon perusta löytyisi materiaalisesta evoluutiosta - ikäänkuin olemassaolo/oleminen kehittyisi asteittain fysiikan ja evoluution lakien eli luonnonvalinnan vaikutuksen materiaalisena 'sopeutumana' siinä missä kaikki muutkin materiaaliset oliot - [jos en ole teisti en ole myöskään uskonnollinen panenteisti].

Oleminen [a fortiori: olemassaoleva oleminen eli Jumala] on olevan perimmäinen syy, jota ei voi johtaa mistään - muutenhan se ei olisi syy vaan seuraus jostain itseään ontologisesti perustavammasta.

Tällainen perusta tai ehto ajattelun mahdollisuudelle on episteemistä muttei ontologista antirealismia. Jos et ymmärtänyt tai olet eri mieltä, voidaan lopettaa tähän, koska emme puhu samasta asiasta eikä intuitiivisia käsityksiämme järjenkäytön tavasta ja mahdollisuusehdoista voi mitenkään sovittaa yhteen.

Sinä elät imaginaarisessa maailmassa, sillä se, joka luulee kykenevänsä kuvaamaan Jumalaa 'oikein', on langennut imaginaarisen interpellaation ansaan fantisoimalla, että Jumala olisi jotain hänen itsensä kaltaista, koska täydellistä toiseutta [reaalinen] on mahdoton kuvitella ilman samaistumista/identifikaatiota [ikäänkuin omana kuvana] tai tietää muuten kuin symbolisena fiktiona [Jumala Sanana ja Lakina].

Niinpä imaginaarinen usko jos mikä on antropomorfismia ja projektiota, koska se tekee Jumalasta oman kuvansa [jumalanpilkkaa siis!].

Symbolinen [fiktiivinen] usko, jota fideismi tai ateismi [uskon kielto] edustavat sen sijaan tunnustaa tiedon [ja siten myös uskon] mahdollisuuden rajat eikä suostu puhumaan [tai ainakin varoo puhumasta] sellaisesta, josta ei mitään voi tietää.

Toki jokainen saa kuvitella niin paljon kuin haluaa, mutta silti uskon ja imaginaation sekoittaminen keskenään on aina sukua animismille ja ylipäätään polyteismille.

Valitan - mutta en voi uskoa niinkuin panteisti ja polyteisti ja nimenomaan sen vuoksi, että haluan uskoa [tai epäuskoa] enkä haaveilla itseidenttisyydestä [joka on harhaa] ja siten kuvitella jonkin käsittämättömän olion [ikäänkuin Jumala olisi olio] kaltaisekseni.

2

Tiedon looginen mahdottomuus Jumalan suhteen voi siis johtaa yhtä hyvin fideismiin kuin ateismiinkin, mutta ei panteismiin ja polyteismiin. Huomautan, ettei tämä päättely ole agnostismia, koska kaikki todennäköiset evidenssit Jumalan olemassaolon puolesta tai sitä vastaan ovat [jopa tieteellistä] imaginaatiota, joka legitimoidaan aina uskona [symbolisen rekisterin] Suureen Toiseen - olipa tuo toinen sitten Jumala [kosmis-moraalisena auktoriteettina] tai Tiede [tieteen 'objektiivisena' asiantuntija-auktoriteettina].

Sanoudun irti tällaisesta uskosta/epäuskosta ja perustelen oman fideismini/ateismini deduktiivisesti negatiivisella [apofatisella] teologialla.

Mystiikka voi olla hyväksyttävää vain apofatisista lähtökohdista. Lukekaa esim. Greorios Nyssalaisen analyysia mystisestä kokemuksesta eli Mooseksesta Siinain vuorella. Lopussa on on aina pimeys, joka muuttuu valoksi - jos on muuttuakseen - - .

Mitään positiivista evidenssiä Jumalasta meille ei kuitenkaan voi olla olemassa. Emme siis myöskään voi tietämällä tietää, oliko Mooses Jumalan kohdatessaan a] mielenhäiriössä, b] keksikö hän tarinan Jumalan kohtaamisesta ja tämän käskyt omasta päästään [siis valehteli Jumalasta puhuessaan] vai c] puhuiko hän niin sanotusti totta/rr.

Onhan tuossa jo kolme vaihtoehtoa - niinkuin pluralistisina aikoina kai olla pitääkin. Nyt eikun suvaitsevaisuutta kehiin ;\].

*

http://actuspurunen.blogspot.com/2011/08/aarellisyys-ei-ole-asia-joka-estaa.html

http://www.cla.purdue.edu/english/theory/psychoanalysis/lacanstructure.html

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jacques_Lacan

http://fi.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fundamentaaliontologia

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pantheism

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fideism

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jean-Luc_Marion

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Panentheism

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Apophatic_theology#In_the_Christian_tradition

http://looneytunes09.wordpress.com/2011/07/29/part-ii-back-in-time-brings-blackness/

http://www.shaeqkhan.com/2010/03/20/the-fibonacci-obsession/

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fibonacci_number

http://mathforum.org/mathimages/index.php/Fibonacci_Numbers

http://taicarmen.wordpress.com/2011/03/08/the-connectivity-of-form-finding-meaning-in-the-golden-mean/

http://www.tiede.fi/keskustelut/biologia-ja-ymparisto-f9/pyha-geometria-fibonacci-ja-phi-t36007-15.html

August 29, 2011

Don Juanin loistava pahuus

Don Juan ja David Bentley Hart

*

[Kielimafia lisäsi tarkennuksen kohtaan 3 - 4.9]

I

Don Juan hahmo ilmaisee hyvin barokin ajan elämänkokemusta, hämmennystä sen suhteen, onko äärimmäinen nautinnollinen elämä samalla äärimmäisen tyhjää. Hahmo esiintyy ensimmäisen kerran Tirso de Molinan näytelmässä El Burlador de Sevilla y convivado de piedra (Sevillan pilkkaaja ja kivinen vieras).

Don Juan on naisten viettelijä, joka kutsuu luokseen erään viettelemänsä naisen isän kivisen hautapatsaan, ja kun tämä sitten tuleekin, hän vie Don Juanin mukanaan helvettiin.

Voimme kysyä, mikä Don Juanin tarinassa on modernia. Eikö antiikissakin ole lukuisia viettelytarinoita ja viettelijähahmoja; eikö tällainen ole esimerkiksi Zeus itse, jolla on lukemattomia naisjuttuja kuolevien ja kuolemattomien kanssa?

Ero antiikin ja modernin tarinan välillä on juuri siinä, että Zeus ei antiikin perspektiivistä katsoen ole viettelijähahmo, koska hänen naisseikkailunsa nähtiin yksittäisinä tekoina, joihin oli syynä jumalaista alkuperää oleva (Afroditen aiheuttana) rakkauden intohimo, jonka uhreiksi kuolemattomat voivat joutua yhtä hyvin kuin kuolevaisetkin. Toisin sanoen henkilön tekojen syynä ei ole hänen taipumuksensa tai luonteensa vaan hänen joutumisensa tiettyyn objektiiviseen asiaintilaan. Modernissa sen sijaan rakkausseikkailu on ihmisen oma valinta, johon hänellä on tai ei ole luontainen taipumus.

Don Juan-myytti rinnastuu Faustiin eräänlaisena maailman valloittamisen ja omien voimien mittelemisen myyttinä sekin. Myöhemmissä kirjallisissa tulkinnoissa Don Juan on nähty usein romantisoiden ideaalin etsijänä, joka ei voi tyytyä reaaliseen todellisuuteen, tai rakkauteen kykenemättömänä ja siksi yhä uusiin viettely-yrityksiin tuomittuna. Hänestä on tullut kuten Faustista hahmo, johon voidaan suhtautua sympatialla.

II

1

A SPLENDID WICKEDNESS

David Bentley Hart considers the moral significance of Don Juan's amoralism.

Publication: First Things

Author: Hart, David Bentley

Date published: August 1, 2011

The literature of Spain's "Golden Age" produced two figures - Don Quixote de La Mancha and Don Juan Tenorio - who quickly escaped the confines of the works that gave them birth and took up exalted but previously unoccupied stations in the Western imagination. Each soon became as much an archetype as an invention, somehow existing beyond his written story. In either case, moreover, the result was rather curious, since neither figure in his final form was so much a mythic aggrandizement of the literary model as an almost total inversion.

The mythic Quixote - the paladin of the impossible, the heroic dreamer, the holy fool whom Unamuno regarded as a kind of "saint" and "Christ"-is not really the Quixote of Miguel de Cervantes. The old "knight of La Mancha" was intended by his creator principally as an object of mirth. By the same token, the mythic Juan - the irresistible seducer, the apostle of lighthearted satyriasis, the proud rebel against society and heaven, whom Kierkegaard saw as the perfect personification of sensuousness and Camus saw as a hero of the absurd - is not really the Juan created by Tirso de Molina in El Burlador de Sevilla y convidado de piedra. Tirso's character is definitely a roué, but hardly a virtuoso of the boudoir. His appetites are lavish, but his methods are generally jejune, and his conquests are the results not of personal magnetism but of cunning opportunism. True, he bravely defies the laws of God and society - not, though, as a philosophical rebel, but rather as a moral oaf.

Today, both figures have withdrawn to a considerable degree from popular awareness, especially outside the Spanish-speaking world; but Quixote's myth still retains a concrete shape, and something of his story remains fixed in our minds. Juan, by contrast, has disappeared almost entirely, or been replaced by a vague and insipid popular image of some primped and purring amorist who bears no real resemblance to him at all. And yet, until less than a century ago, his story was by far the better known, more influential, and more vital of the two. For three hundred years, playwrights, poets, and essayists returned to him not only regularly but almost obsessively. And then, all of a sudden, he was gone. What became of him?

There is an immediately tempting answer, but it seems to me inadequate. Quixote has survived the ravages of time chiefly because he is of his nature timeless; he enchants us with his absolute exorbitance, his ability to inhabit a parallel reality of his own, corresponding wholly to his own poetic and moral creed. He floats high up above any age as a kind of shimmering antithesis, perennially impossible, beautiful, and moving; indeed, he is more attractive the more implausible his values come to seem. Perhaps, then, we could by analogy assume just the reverse in the case of Juan: Perhaps today we live in an age of such pervasive "Donjuanism" (understood simply as insouciant sensualism) that the original has lost his power to scandalize, surprise, or even interest us. I think, though, that this answer rests on an irreparably flawed premise.

The reality of the matter is quite the opposite: Juan is not familiar to us at all today, and the reason our cultural imagination no longer has much room for him - -and would certainly be incapable of producing another figure like him - is that he, far more than the buoyantly eternal Quixote, is a figure fixed in a particular cultural moment. He is not timeless, but only epochal. He personifies a long but circumscribed historical episode, apart from whose ambiguities and energies he is unintelligible: that twilight interval stretching between the late Renaissance and contemporary secular modernity. Juan was the greatest immoralist of European literature precisely because he served as the negative image of the moral convictions and capacities of his time and place, the exemplary contradiction of an entire and coherent vision of the good, whose story magically combined a certain nostalgia for fading cultural certitudes with a certain cynicism toward them. So, when the values of his time disappeared, he dissolved with them.

In truth, if he could speak to us today as clearly as he did to earlier generations, it would not be in the amiable tones of someone familiar to us but in a distant, almost prophetic voice, full of ironic moral reproach. He would tell us not of ourselves - of either our virtues or our vices - not even satirically. Instead, he would remind us of a vanished magnificence, inseparable from a now largely abandoned conception of what it is to be human.

Unlike Don Quixote, who made his debut in a work of genuine literary genius, Don Juan has always somehow exceeded the occasion of his first appearance. In fact, we are not even sure when he really did first appear. Tirso de Molina (the nom de guerre of Gabriel Téllez, a monk in his day job) wrote most of his plays between 1605 and 1625; but he did not include El Burlador de Sevilla in any collection of his works, so we do not know when - or perhaps even if - he wrote it. More to the point, as entertaining as Tirso's play is, it is neither an extraordinary literary achievement nor even necessarily the most authoritative version of the tale. Its chief importance lies in its having initiated a theme that for three centuries of European letters seemed nearly inexhaustible, and for having established the canonical pattern of Juan's tale as it was told in most subsequent renderings up to the time of Mozart's Don Giovanni. In the end, then, "Juan as such" is an abstraction, derived from a positively oceanic literary history, of which any distillate is necessarily only very partial. He has no single, wholly solid form, but comes to us in a series of shifting translucencies.

Certain essential elements of the character are there from the very beginning, however, if only in an inchoate way, and endure throughout his literary career. The most important, and by far the most attractive (literarily speaking), is his proud impenitence. This in itself is odd. Tirso intended his protagonist as a cautionary example of the vicious and debased state to which unrestrained appetite reduces a soul. His Juan, far from being meant to engage our sympathy, is for the most part rather uninteresting: an ordinary profligate, cad, and sexual predator of noble extraction, with sufficient means to pursue his desires and without any discernible sign of a conscience to impede the pursuit. When he comes to a bad end, we are supposed to recognize it as divine justice and to concur with the verdict.

But that is not quite what happened. Inadvertently, Tirso endowed his character with a faint but invincible glamour. A man so recklessly devoted to his own passions that he can careen knowingly into the very embrace of hell, without wavering from the course his own character steers him on, is intrinsically interesting. However repellent we may find his deeds, we cannot help but feel a certain exhilaration at, and even envy of, his unconquerable exuberance. And this, more than anything else, accounts for the figure's profuse longevity in European letters. It was Juan's insane inflexibility of will that almost all later versions of the tale, even when they were not intended to do so, seemed to celebrate.

But, again, Tirso's play, as he wrote it, is essentially a morality drama. It begins late at night in the royal palace of Naples, where Juan has gone disguised as one Duke Octavio so that he can bed the duke's fiancee, the Duchess Isabela. She discovers the imposture too late to save her honor (such as it is), but before Juan can elude the guard; he does eventually escape, though, his true identity still undiscovered, and flees the city. Isabela, to save face, allows Octavio to bear the blame.

En route to Seville, Juan and his servant Catalinón ("coward") are shipwrecked but manage to swim to shore, where Juan promptly seduces, enjoys, and abandons the fisherman's daughter who comes to his aid. On reaching Seville, Juan finds that report of his Neapolitan adventure has reached the court of Castile, as has Duke Octavio, but fortunately the duke still does not know who cuckolded him. The king, however, guesses easily and commands Juan to marry Isabela - whom he has summoned from Naples - and grants the duke the hand of a certain Doña Ana as a consolation. But Ana is in love with a certain marquis, and Juan, knowing this, disguises himself as her beloved and attempts a nocturnal assault on her virtue, of the sort that had worked so well with Isabela. Ana is not fooled, however, and calls for help. When her father Don Gonzalo, commander of the Order of CaItrava, comes to her rescue, Juan kills the old man and flees. The marquis is arraigned for the murder. Later, passing through the countryside, Juan happens upon a peasant wedding feast, seduces the new bride with promises of marriage, deflowers her, and then slips away back to Seville.

There, however, forces are gathering against him: Isabela, Octavio, the fisherman's daughter, the marquis, the peasant bride, and even Juan's own father, Don Diego. Meeting Juan in a church, Catalinón warns his master of the danger, but Juan is unimpressed. Then, in a side chapel, he comes upon a statue of the murdered commander and, mockingly pulling its beard, invites it to dinner. When, surprisingly, the statue appears for its meal, Juan betrays only momentary consternation and then plays host with all the panache one would expect of a true hidalgo. He even takes the statue's proffered hand and accepts its invitation to dine the following night in Don Gonzalo's chapel. Juan confesses to himself that the stone had burned his hand and that he had felt fear, but he quickly shrugs that off as something unmanly.

The next night, he goes to dinner as appointed, dragging Catalinón along; there, after the amenities have been observed (a dish of vipers, a cup of gall), the statue takes Juan again by the hand and draws him down to hell. Juan cries out in pain, and even asks to be shriven by a priest, but otherwise meets his end bravely. In the final scene, Don Diego's honor is restored, Octavio is reunited with Isabela, and the marquis is returned to Ana.

Anyone familiar with most of the notable versions of the tale from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries will recognize almost all the standard elements here, however much names and details may shift about in various tellings. Only a few additional features needed to be added by Tirso's successors. In the anonymous II convitato di pietra, from the 1650s, Juan's servant (now called Passarino) for the first time both produces the famous list of his master's conquests and cries out in despair for his wages when his master is taken to hell. In the various versions of the tale that entered the repertoire of the commedia dell'arte, the elevation of the story's comic aspects over the tragic became more pronounced. And the French playwright Dorimon penned a version in which Juan treats his own father so callously that the old man dies from emotional shock, which may be how the element of parricide entered the standard narrative.

The most original seventeenth-century treatment of the story is, without question, Molière 's Dom Juan ou Le Festin de pierre (1665), which, even if it is not a work of genius, is the work of a genius, and is the first treatment of Juan that is of genuine literary interest. Still, it has all the appearances of a work Molière might have concocted over a few winedrenched afternoons. It is written in prose, its structure is sprawlingly haphazard, and its abrupt finale is as nonchalant a piece of deus ex machina as any hack might have flung in the face of his audience. But the dialogue is hilarious, the characters have real dimensions, and the language is frequently splendid. Molière gave the world the French Juan: acerbic, coolly proud, skeptical, nonchalantly raffish, earnestly frivolous, naturally polygamous, a bad but not particularly abusive son, a duelist but not a murderer.

The most arresting seventeenth-century version, however, is certainly Thomas Shadwell's lurid and demented extravaganza, The Libertine (1676), whose "Don John" is not merely a burlador or rake, but something like Satan's less reputable twin brother. The antinomian monster at the center of this play is a prolific murderer and rapist, who has murdered his own father and is laying plans to rape several nuns; he is also a thief, a blasphemer, and - almost as bad - a philosopher. As he and three equally evil boon companions rampage across the stage, committing one atrocity after another with delirious gaiety, they also spin out elaborate but perfectly cogent rational justifications for their actions, of an almost proto-Nietzschean kind. And, even on the brink of damnation, amid a roiling phantasmagoria - ghosts of his victims, devils, the living statue, hell's fire - he expresses neither fear nor remorse but goes to his perdition proudly affirming his unshakable loyalty to himself, with a courage so insane it almost deprives hell of any significance. When the curtain falls, one is left wondering whether the devil is ready to receive him, or might rather be too shocked at his morals.

Molière's and Shadwell's renderings were aberrations, however. In the almost countless versions that appeared between Tirso's play and Da Ponte's libretto for Don Giovanni (1787), Juan remained very much the villain Tirso had made him: a violent, rapacious, unreflective, and unrepentant seducer whose fate is both just and satisfying. So he remained in Don Giovanni. And so, but for shifting cultural fashions, he might have remained indefinitely: a perennially popular theatrical motif, but not yet a fully fledged myth.

Something unanticipated, however, happened to Juan as he moved into the third century of his literary existence. The tacit sympathy he had perhaps always enjoyed among the patrons of the theater began to reshape his narrative explicitly. In the Romantic Age, he became more glamorous, was invested with deeper pathos, and was finally burdened with profundity. He remained a seducer, but now one to whom women were naturally drawn; and his desire for women, which had formerly been simple animal appetite, now took on the character of heroic "striving," an insatiable longing for the perfection of love or deification of the passions. The Romantic Juan actually loved women, or at least loved "woman" as an ideal, and in despair of finding the ideal embodied fled from one woman to another. So, at least, said E. T. A. Hoffman in 1814. In 1830, in The Stone Guest, Alexander Pushkin depicted Juan as a womanizer, but one who can unexpectedly lose his young, impetuous heart to Anna. Byron's Juan (who really little resembles the Juan of the classic narrative) is a figure of almost infinite romantic vulnerability. In 1844, Nikolas Lenau portrayed Juan as a disillusioned erotic idealist, embittered and defeated by the purity of his own passions.

Juan became, in short, a symbol of the rebellion of sentiment against society or heaven, and thus a tragic lover whose soul was worth contending for. Now his damnation, rather than being merely the condign consummation of a rogue's career, became the tale's crucial moment of philosophical truth. Some playwrights went so far as to rescind the sentence in the final moments. Others sent Juan to hell, but almost in triumph. Hell seemed merely to endow him - his defiance, his virility, his freedom of will - with a dark Miltonic grandeur. This tendency reached a quiet climax in Baudelaire's poem "Donjuán aux enfers," which shows Juan being ferried across the waters of death by Charon, surrounded by the specters of his many victims, but remaining utterly impassive all the while:

Mais le calme héros, courbé sur sa rapière,

Regardait le sillage et ne daignait rien voir.

(But the hero, unperturbed, leaning upon his rapier, Gazed at the wake and deigned to see nothing).

When Yeats, in 1914, described the eunuchs in hell's street enviously watching mighty Juan riding by, he was making use of what by then was something of a literary commonplace.

The Romantic eye was particularly suited to see something in Don Juan more interesting than had been noticed in the past: some deeper significance lurking behind all that romping, glittering, ravenous exuberance - some secret sadness or divine discontent. But the more the Romantics encumbered his story with "meaning" by converting his unreflective sybaritism into a Promethean defiance of the gods, the more they deprived him of his few engaging qualities: mirth, frivolity, childish pride, thoughtless wickedness. Most egregious in this respect were those poets and playwrights who saw some sort of deep analogy between Don Juan and Dr. Faust - on the grounds that both go to hell, or nearly do, and that both are striving after something, whether absolute knowledge or absolute sensuousness. Nicolas Vogt actually conflated the two figures in his immense, ludicrous, mercifully unfinished Gesamtkunstwerk from 1809, Der Färberhof. Christian Dietrich Grabbe, in 1829, produced Don Juan und Faust, a vast, seething swamp of large ideas, exaggerated passions, incoherent action, crushing monologues, deranged lyricism, and adolescent moral nihilism, which is somehow made even more unbearable by its numerous moments of poetic brilliance. In this play, Faust and Juan - each magnified or reduced to a symbol of a certain kind of spiritual temperament - vie for the love of Anna, whom Faust ends up killing. Both of the protagonists go to hell - Faust in remorse, Juan in defiance - but only in order to prove that Satan is more powerful than either.

And it was not only Germans who brought the two figures together. Some French authors did it as well, though with (needless to say) a lighter touch: Eugène Robin in 1836, in his poem Livia, and Théophile Gautier in 1838, in his poem La Comédie de la mort. And various later versions of Juan's story were influenced by Goethe's Faust even when the good doctor made no personal appearance on stage. Alexei Tolstoy's poem Don Juan (1860) includes both a prologue in heaven and a final redemption scene. And the dénouement of José Zorilla's glutinously pious (and still popular) Don Juan Tenorio (1844) - in which Juan is saved from hell at the last moment by the pure spirit of the one woman he truly loved - is a particularly unfortunate encore on the part of Goethe's Eternal Feminine.

By the end of the nineteenth century, I think it fair to say, the myth was fully formed. None of the twentieth-century revisions of the story made any actual contributions to the legend. The best of them - Shaw's Man and Superman, Rostand's underrated La Dernière Nuit de Don Juan, Frisch's Don Juan oder die Liebe zur Geometrie - were sardonic commentaries on a legend already fully formed. Each starts from the presupposition that we already know who Don Juan is and what he represents, and that we will therefore be able to appreciate the playwright's comic or caustic variations on the story. And then, around about midcentury, Juan's tale ceased altogether to generate any significant works of literature. A few philosophers continued to write about him for a while, a few psychologists - perhaps a fate worse than hell - seized on him as a pathology or psychological type. And then he more or less receded permanently to unvisited library shelves, a superannuated archetype.

Again, why was this so? And, again, the obvious but inadequate answer would be that Juan's ability to fascinate, exhilarate, and alarm has been lost in our age of unrestrained sensuality, voluntarism, glandular liberation, and relaxed consciences. Not that such an answer is wholly false: Certainly the more picaresque side of Juan's adventures - the veil of night, the cloaked figure stealing over balconies and through windows, the sordid incognito - seems only quaint in light of today's morbidly austere and functionalist venereal aesthetics. Contemporary erotic etiquette, even among the young, has so drained physical love of its enticingly forbidden and urgent quality, and so dispelled its atmosphere of rapturous risk, moral uncertainty, tantalizing mystery, and irresistible yearning, that the actual quantum of pleasure in the transaction is often, one imagines, diminished to a very transitory set of neural agitations. One should speak a reverent word or two for the aphrodisiac virtues of emotional innocence and inhibition. Fruit stolen after midnight from a walled and moonlit garden has a sweetness that the riper fruit purchased at midday in the market lacks.

All of this being granted, however, there is more to the mystery of Juan's disappearance than that. For one thing, his was never just the story of a selfindulgent hedonist on the prowl; it always possessed a larger metaphysical significance. No matter how great Juan's metamorphosis had been in his translation from Baroque to Romantic literature, his legend continued throughout to speak of transgression, of the power of unrestrained desire, and of the spiritual paradox of free will. Behind the tale's winsome glitter or lurid glare, there was always the outline of a sacred or demonic drama, however the sympathies of the poets may have shifted one way or another over time.

Moreover, if one looks back over all the figure's variations - the Latin or Teutonic Juan, the Baroque or Romantic Juan, Juan the pure voluptuary immune to disenchantment, or Juan the shattered idealist of love - one sees that two crucial elements remain fairly constant: First, he is indeed a true sensualist, delighting not only in sex, but also in food, wine, poetry, and song; and, second, he is truly courageous to the last, going to his doom gladly rather than attempting a repentance incongruous with his nature. These are obvious points, perhaps, but they should be understood in very particular ways. To say he is a sensualist is to say he is both servant and master of the senses, in all their elemental power. And to speak of his courage is to speak not of his spiritual rebellion or cosmic despair but only of his exultant awareness of the inalienable power of his own will. And, on both these points, Donjuán is a figure curiously alien to modern sensibilities.

That may seem an odd assertion, admittedly. We tend to think ours is a hedonistic age, and individual liberty is certainly its highest value. But distinctions should be drawn. For one thing, though there are no doubt many sensualists among us, ours is by no means a sensualist culture. Genuine sensualism requires a fairly healthy sense of natural goodness, and some developed capacity for discrimination. Late Western modernity, especially in its purest (that is, most American) form, certainly values the available and the plentiful, but not necessarily the intrinsically pleasing. As far as the actual senses are concerned, ours is in many ways a culture of peculiar poverty, evident even - perhaps especially - in its excesses. The diet produced by mass production and mass marketing, our civic and commercial architecture, our consumer goods, our style of dress, our popular entertainments, and so forth - it all seems to have a kind of premeditated aesthetic squalor about it, an almost militant indifference to the distinction between quantity and quality.

There has always been, of course, a division between popular and high culture, but usually also some continuity in kind between them. Today it often seems as if truly aesthetic values have been moved out of the social realm altogether, into ever smaller private preserves. Certainly they are not central to our concept or experience of the common good, even though we may occasionally make a public pretense of caring about such things. Our culture, with its almost absolute emphasis on the power of acquisition, trains us to be beguiled by the bright and the shrill rather than the lovely and the subtle. That, after all, is the transcendental logic of late-modern capitalism: the fabrication of innumerable artificial appetites, not the refinement of the few that are natural to us. Late modernity's defining art, advertising, is nothing but a piercingly relentless tutelage in desire for the intrinsically undesirable.

True sensualism, by contrast, is a longing for real intimacy with the world of sensible things. What Juan desires is desirable of itself, and his appetency is a real expression - however corrupt - of the dignity and loveliness of incarnate life. He is a thoroughly unethical soul, but his way of life is still an ethos, not simply a state of unremitting distraction. When he pursues or embraces the phenomenal aspect of what he desires, he at least seeks some kind of communion with the thing in itself, some capture of the whole nuptial totality of form and matter. Late modernity prepares us to live far more contentedly in their divorce: material goods without formal beauty, phenomenal diversions without material depth, nervous stimulation without sensuous enrichment. If our style of life is a materialism, it is of an oddly disembodied kind, and does more to shield us from the senses than to liberate them.

By the same token, Juan's pride and willfulness are more than mere bourgeois self-indulgence or latemodern narcissism. His self-love is destructive, even demonic, but it certainly is not petty. Frivolous as he is, his tale is cast against a backdrop of cosmic significance, because he still inhabits a coherent moral universe. He knows the rules that govern it and by the end certainly understands the consequences of violating them, but he rejects the moral order nonetheless. Even setting aside all those Romantic exaggerations about Juan's Promethean or Luciferian defiance of God, one can still say that his unwillingness to repent and his insistence on accepting that final dreadful invitation actually affirm both the existence of divine law and the godlike power of the soul to choose its own destruction.

In the end - and this is the principal reason his myth has lost its power for us - his tale is a volatile combination of the most exalted idealisms and the coarsest cynicisms of an age of radical change. He was born in the waning light of the last epoch of triumphal Christian humanism, the inverted double of the Renaissance Man, and his story was a satire in the full Attic sense: a satyr-play concluding a glorious but exhausted drama, at once mocking and celebrating the cycle it brought to a close. Hence his long progress from worthless rogue to champion of the passions to psychological cliché to obsolescence perfectly symbolizes the transition from the premodern to the postmodern cultural imagination, moral and aesthetic: from faith to disenchantment to resigned equanimity. He could not have been invented earlier than he was, and he could not have endured any longer than he did. His proper element was that long cultural gloaming in which the old moral metaphysics retained its formal authority, but not its credibility.

Over those few brief centuries, all the old paradigms would be entirely recast: The mechanical philosophy would transform nature from a living theophany into a spiritless machine; secularization would subordinate all human associations to the bare dialectic between the state and the individual; the ideology of market economics would reduce human community to the impersonal algorithms of private interests; Darwinian biology (both as science and as a metaphysics) would absorb human nature into the mechanistic narrative; and so on. In the end, modernity would achieve its inevitable revision of our understanding of ourselves and our world, and the mythic Juan - personifying the irresoluble tension between what was passing away and what was coming into being - would at the last quietly melt away. His myth vanished because it was essentially a myth of withdrawal; his Odyssey through European letters was, from the first, a single long recessional.

So I return to where I began. The figure of Don Juan is an imaginative impossibility in our time because he comes from a period in which the human being was understood not merely as a biological machine, generated randomly out of the incessant flux of an aleatory universe, but as a radiant and terrible enigma, dangerously and daringly poised between beast and angel, hell and heaven, the elemental abyss and the infinite God: a period in which it was still just possible to believe that human freedom was not merely the all-but-illusory residue of a random confluence of mindless physical forces and organic mechanisms, but a glimpse of the transcendent within the world of matter. Juan's wickedness, by its sheer garish or stylish flamboyance, still reflected an exalted - and not merely sentimental - sense of human dignity. Even his sexual esurience was not just brute impulse, but the darkly distorted image of an angelic liberty.

This cannot be the case for us. Our culture is not subject to the torments of immutable moral laws or to the allure of the transcendent good: The terror and the ecstasy of the absolute are not the deep, flowing springs of our shared conscience. In such an age, there can be no such thing as splendid wickedness. If we do not see ourselves in the light of the Good beyond being, nothing in our nature can be cast in sufficiently striking relief. And now that so many deeds that once were thought to place a soul in the balance have become matters of moral indifference, most of the choices we make are by definition unimportant, and the heroism or antiheroism of moral choice is all but impossible. This is simply the modern condition; perhaps it is a blessing. It means, however, that not only our virtues, but also our vices, have been robbed of their poetic resonances. Individual writers will, of course, always be able to dream up deplorable but charismatic rogues with enormous appetites, like George MacDonald Frasier's Flashman or Roald Dahl's Uncle Oswald; more-ambitious artists may produce the occasional jubilant amoralist with a gift for momentarily transforming the bleak absurdity of existence into a rude carnival, like Alvaro Mutis' Maqroll the Gaviero. But our shared cultural imagination has no real place for a moral and metaphysical drama like Juan's.

As I have said, the figure of Quixote abides because he is borne aloft by his beautiful and mysterious timelessness. Juan was never timeless. He was weighed down from the beginning by a whole history of cultural dissolution. And now, in his majestic frivolity and obdurate impenitence, he is beyond our ken. If we could grant him a few moments of serious attention, however, he would remind us of a world in which the moral meaning of the universe could be read in a single soul, because a sublime and integral sympathy united them, as macrocosm and microcosm, totality and epitome. And still, whether we are conscious of it or not, the heroic scope of his negations rebukes us with the image of a human grandeur perhaps no more unattainable than in the past, but certainly far more unimaginable. Any modern attempt at the invention of a Don Juan, or of any similar archetype of animal vitality or spiritual revolt, would fail almost inevitably. The figure we would produce would have no meaning now: no depth, no height, neither deformity nor beauty. Compared to Juan, whoever might emerge from our common cultural imagination to take his place would simply be too damned boring - or, more precisely, too boring to be damned.

Author affiliation: David Bentley Hart is contributing editor of First Things and author of Atheist Delusions (Yale).

Read more: http://periodicals.faqs.org/201108/2410208671.html#ixzz1WB3BqPi5

2

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f6IdKGp3fAk

The Wabash Commentary is hosting a talk by David Bentley Hart. The title of his talk is 'Don Juan as Moralist' - [April 18, 2011].

3

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dK1_vm0FMAU

'The Commendatore Scene' [loppukohtaus] - Don Giovanni

*

In the modern opera house the final curtain falls upon this scene. In the work, however, there is another scene in which the other characters moralize upon Don Giovanni’s end. There is one accusation, however, none can urge against him. He was not a coward. Therein lies the appeal of the character. His is a brilliant, impetuous figure, with a dash of philosophy, which is that, sometime, somewhere, in the course of his amours, he will discover the perfect woman from whose lips he will be able to draw the sweetness of all women. Moreover he is a villain with a keen sense of humour. Inexcusable in real life, he is a debonair, fascinating figure on the stage, whereas Donna Anna, Donna Elvira, and Don Ottavio are mere hinges in the drama and as creations purely musical. Zerlina, on the other hand, is one of Mozart’s most delectable characters. Leporello, too, is clearly drawn, dramatically and musically; a coward, yet loyal to the master who appeals to a strain of the humorous in him and whose courage he admires.

4

Don Giovannista Facebookiin

Don Juan/Giovanni ei kadu tekojaan komentajan 'henkipatsaan' sitä kysyessä, mikä merkitsee, että hän tällä tavoin tulee katumattomassa uhmassaan vapaaehtoisesti valinneeksi kuoleman ja nimenomaan helvetin eikä pelastusta, jonka katumus vielä viimeisenä vaihtoehtona saattaisi hänelle mahdollistaa.

Don Giovannin radikaalissa pahuudessa [täysin riippumatta närkästyksestämme hänen tekojaan kohtaan] on tiettyä moraalista ylevyyttä - luonteen suuruutta ja siten jopa hyveellisyyttä - olkoonkin, ettei Don Juan koskaan voi toimia positiivisena ihanteena - ainoastaan loistavana esimerkkinä mielen lujuudesta henkilökohtaisen päätöksen tasolla.

Don Giovannin katumaton ehdottomuus muistuttaa perverssillä joskin ylevällä tavalla käänteistä mutta yhtä lailla perverssejä piirteitä omaavaa fanaattista uskon marttyyriutta eli patologisen ehdotonta hyvettä [moraalia].

Don Giovannin barokkimaista pahuuden 'puhtautta' ['puhtaus' ei siis merkitse moraalista hyväksyntää vaan ko. asenteen subjektiivisen vilpittömyyden ja aitouden tunnustamista] ei liberaali-demokraattisesta sivilisaatiosta kuitenkaan enää löydä, koska se on diagnosoitu psykopatiaksi, jota voi kuitenkin juuri tuon kliinis-moraalisen etäisyyden vuoksi käsitellä fiktiivisten hahmojen puitteissa.

Ja miten on - eikö koko nykyinen maailmamme ole täynnään don-giovanneja, joista ei kuitenkaan enää löydä mitään moraalista suuruutta? - [Eikä sellaista edes voi löytää, koska Don Giovannin intohimoisen moraaliton sensuaalinen egoismi on demokraattisen yhteiskunnan tabu, jota se väistämättä joutuu läpielämään fantasioissa ja etenkin porno- ja väkivaltaviihteen muodossa].

Mutta ehkäpä juuri faktionaalis-viihteellisten murhaajien metsästys valtaisaan suosioon yltäneessä dekkari-kirjallisuudessa ja toisaalta yhtä lailla valtaisan suosion saavuttaneessa uudentyyppisessä viihde-genressä eli tosi-teeveen rikos- ja poliisidokumenteissa ilmentää eräänlaista moraalisen pahuuden banalisoitumis-prosessia, joka tapahtuu [hegeliläisittäin ja freudilaisittain] käänteisyyden, etäisyyden ja turvallisen faktion kautta - kuitenkin vulgaareihin väkivalta- ja seksi-fantasioihin vetoamalla ja niitä hyödyntämällä.

Ehkäpä Don Juan vakavasti otettavan valinnan tekevänä immoralistina todellakin on mahdoton modernina aikana - tosin paradoksaalisella tavalla. Don Juan edustaa liberaali-demokraattiselle järjestykselle aidosti vaarallista tyyppiä: hänet on modernismin kehittyessä torjuttu ja fiktioitu alkuperäisestä eli 'autenttisesta saatanallisuudestaan' tabuksi, jota kuitenkin viihteessä ja fantasioissa [joita tosi-teevee ovelimmin stimuloi] jatkuvasti kierrämme ja rikomme, mikä [hegeliläisittäin ja freudilaisittain] merkitsee, että Don Juan on paradoksaalisesti muuttunut juuri modernin ihmisen itsensä reaaliseksi hahmoksi, jota tämä moderni kansalainen ei kuitenkaan tabun vuoksi itsekseen tunnista - [a) virallinen eli symbolinen imago: pitää olla suvaitsevainen ja humaani demokraatti, b) reaalis-imaginaarinen imago: vulgaari ja lattea egoismi].

Tällainen ihminen on yhtä aikaa vulgaari ja banaali - liberaalis-subjektiivisen valinnan vapauden ja demokraattisen moraalin tuotos: itseään häpeämätön ja itseään 'toteuttava' nautinto-onnen addikti, jolta kuitenkin puuttuu Don Juanin uskonnollisen ja yhteisöllisen moraalin ylittävä - kaiken läpäisevä ja häikäilemätön sensuaalisen subjektiivisuuden ehdottomuus - suorastaan loistava sensuaalinen pahuus, josta on tullut maailmankatsomus.

Tällainen ajattelutapa oli mahdollista kohdata vakavasti moraalis-esteettisenä tyyppinä vain renessanssiin ja uskonpuhdistukseen jyrkän ambivalentisti reagoineen barokin monenlaisten äärimmäisyyksien aikana, mutta jo 1700-luvun eli universaaliin valistukseen ja moraaliin pyrkivän vuosisadan jälkeen Don Juan alkoi transformoitua erottamattomaksi osaksi modernin ihmisen identiteettiä, mikä merkitsi yhtä aikaa hänen faustisuutensa [rajoittamaton sensuaalis-tiedollinen ambitio - maksoi mitä maksoi] omaksumista sekä hänen moraalittomuutensa kieltoa [tabu, joka imaginaarisesti ruokkii väkivalta- ja seksi-mielikuvia].

Paria epäilyn hetkeä lukuunottamatta ehdottoman uskon varmuuden sisäistäneestä Jeesus Nasaretilaisesta ja hänen vielä ehdottomampaa subjektiivis-sensuaalista valintaa edustaneesta saatanallisesta 'sukulaisielustaan' Don Juanista on tullut liberaali-demokraattisen massa-sivilisaatiomme tiedostamattomia [ja tavallaan myös tuntemattomia] arkkityyppejä. Niinpä heidän hahmoistaan on myös 'liberaalisti' ja 'demokraattisesti' kadotettu kaikki se alkuperäinen radikaalius ja ylevyys, jota he edustivat - vain vulgaari ja lattea perverssiys on jäänyt.

Mitä kaikkea kertookaan [mm.] Jeesuksen ja Don Juanin hahmojen moraalisen uskottavuuden latistuminen [esim.] kapitalistisen itsetuotteistamisen ehdoilla toimivaksi näennäiskaveruudeksi globaaleissa facebook-yhteisöissä näennäisen transparentista [läpinäkyvästä] ja näennäisen pluralistisesta [monikulttuurisesta] nykymaailmastamme?

Ilmeisesti ja etenkin sen, ettei mitään kerrottavaa enää juurikaan ole eikä tule. Historia on alkanut toistaa itseään jo niin nopeutuvalla tahdilla, että trendit vaihtuvat ja mikä-tahansa-tuotekierto markkinoilla nopeutuu sen verran merkittävästi, että nykyhetki aivan konkreettisella tavalla muuttuu ikuisuuden kaltaiseksi pysähtyneisyydeksi.

On todella irnoista, että Jeesus ja Don Juan molemmat pyrkivät tavallaan aivan samaan eli ajan pysäyttämiseen ja siten sen ikuistamiseen nykyhetkessä. Jeesus julistamalla ja odottamalla Jumalan valtakunnan pikaista tuloa [mitä ei koskaan tapahdu empiirisessä maailmassa] - Don Juan yrittämällä saavuttaa maksimaalisen ja äärimmäisen nautinnon lopullinen hetki [jota ei koskaan tule, koska puute/halu ei lopu].

Jeesus ristiinaulittiin [hän tosin nousi ylös taivaisiin]. Don Giovanni joutui helvettiin [omasta tahdostaan].

Entä facebook-kaverit? He saavat tietysti lisää kavereita. Tällä tavoin pyörii uudenlainen 'ihmiskauppa', sillä facebook on kapitalistisen [itse-]tuotteistamisen korkein jalostettu muoto. Ja kun kommunikaatio lopullisesti muuttuu talous-arvotetuksi tavaraksi, loppuu myös aika.

Mutta tässä ei ole enää mitään hyveellistä, ylevää tai syvällistä. Tavara/tuote ei ole enää tahtova olento. Toisin kuin Jeesus ja Don Juan tuotteeksi muuttunut kommunikaatio on saavuttanut ikuisuuden jo eläessään.

*

http://periodicals.faqs.org/201108/2410208671.html

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/David_Bentley_Hart

http://fi.wikipedia.org/wiki/Don_Juan

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Don_Juan

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Don_Giovanni

http://www.musicwithease.com/don-giovanni-synopsis.html

http://nateduffy.blogspot.com/2011/07/don-juan-and-david-bentley-hart.html

http://www.arthis.jyu.fi/kirjallisuushistoria/index.php/12_barokki/2_espanjan_kultaajan_draamaa/barok_1209.htm

http://whatyouthinkmatters.org/blog/article/nietzsches-good-manners

http://www.reform-magazine.co.uk/index.php/2011/07/david-bentley-hart-interview-modernity-recognise-source-its/

*

[Kielimafia lisäsi tarkennuksen kohtaan 3 - 4.9]

I

Don Juan hahmo ilmaisee hyvin barokin ajan elämänkokemusta, hämmennystä sen suhteen, onko äärimmäinen nautinnollinen elämä samalla äärimmäisen tyhjää. Hahmo esiintyy ensimmäisen kerran Tirso de Molinan näytelmässä El Burlador de Sevilla y convivado de piedra (Sevillan pilkkaaja ja kivinen vieras).

Don Juan on naisten viettelijä, joka kutsuu luokseen erään viettelemänsä naisen isän kivisen hautapatsaan, ja kun tämä sitten tuleekin, hän vie Don Juanin mukanaan helvettiin.

Voimme kysyä, mikä Don Juanin tarinassa on modernia. Eikö antiikissakin ole lukuisia viettelytarinoita ja viettelijähahmoja; eikö tällainen ole esimerkiksi Zeus itse, jolla on lukemattomia naisjuttuja kuolevien ja kuolemattomien kanssa?

Ero antiikin ja modernin tarinan välillä on juuri siinä, että Zeus ei antiikin perspektiivistä katsoen ole viettelijähahmo, koska hänen naisseikkailunsa nähtiin yksittäisinä tekoina, joihin oli syynä jumalaista alkuperää oleva (Afroditen aiheuttana) rakkauden intohimo, jonka uhreiksi kuolemattomat voivat joutua yhtä hyvin kuin kuolevaisetkin. Toisin sanoen henkilön tekojen syynä ei ole hänen taipumuksensa tai luonteensa vaan hänen joutumisensa tiettyyn objektiiviseen asiaintilaan. Modernissa sen sijaan rakkausseikkailu on ihmisen oma valinta, johon hänellä on tai ei ole luontainen taipumus.

Don Juan-myytti rinnastuu Faustiin eräänlaisena maailman valloittamisen ja omien voimien mittelemisen myyttinä sekin. Myöhemmissä kirjallisissa tulkinnoissa Don Juan on nähty usein romantisoiden ideaalin etsijänä, joka ei voi tyytyä reaaliseen todellisuuteen, tai rakkauteen kykenemättömänä ja siksi yhä uusiin viettely-yrityksiin tuomittuna. Hänestä on tullut kuten Faustista hahmo, johon voidaan suhtautua sympatialla.

II

1

A SPLENDID WICKEDNESS

David Bentley Hart considers the moral significance of Don Juan's amoralism.

Publication: First Things

Author: Hart, David Bentley

Date published: August 1, 2011

The literature of Spain's "Golden Age" produced two figures - Don Quixote de La Mancha and Don Juan Tenorio - who quickly escaped the confines of the works that gave them birth and took up exalted but previously unoccupied stations in the Western imagination. Each soon became as much an archetype as an invention, somehow existing beyond his written story. In either case, moreover, the result was rather curious, since neither figure in his final form was so much a mythic aggrandizement of the literary model as an almost total inversion.

The mythic Quixote - the paladin of the impossible, the heroic dreamer, the holy fool whom Unamuno regarded as a kind of "saint" and "Christ"-is not really the Quixote of Miguel de Cervantes. The old "knight of La Mancha" was intended by his creator principally as an object of mirth. By the same token, the mythic Juan - the irresistible seducer, the apostle of lighthearted satyriasis, the proud rebel against society and heaven, whom Kierkegaard saw as the perfect personification of sensuousness and Camus saw as a hero of the absurd - is not really the Juan created by Tirso de Molina in El Burlador de Sevilla y convidado de piedra. Tirso's character is definitely a roué, but hardly a virtuoso of the boudoir. His appetites are lavish, but his methods are generally jejune, and his conquests are the results not of personal magnetism but of cunning opportunism. True, he bravely defies the laws of God and society - not, though, as a philosophical rebel, but rather as a moral oaf.

Today, both figures have withdrawn to a considerable degree from popular awareness, especially outside the Spanish-speaking world; but Quixote's myth still retains a concrete shape, and something of his story remains fixed in our minds. Juan, by contrast, has disappeared almost entirely, or been replaced by a vague and insipid popular image of some primped and purring amorist who bears no real resemblance to him at all. And yet, until less than a century ago, his story was by far the better known, more influential, and more vital of the two. For three hundred years, playwrights, poets, and essayists returned to him not only regularly but almost obsessively. And then, all of a sudden, he was gone. What became of him?

There is an immediately tempting answer, but it seems to me inadequate. Quixote has survived the ravages of time chiefly because he is of his nature timeless; he enchants us with his absolute exorbitance, his ability to inhabit a parallel reality of his own, corresponding wholly to his own poetic and moral creed. He floats high up above any age as a kind of shimmering antithesis, perennially impossible, beautiful, and moving; indeed, he is more attractive the more implausible his values come to seem. Perhaps, then, we could by analogy assume just the reverse in the case of Juan: Perhaps today we live in an age of such pervasive "Donjuanism" (understood simply as insouciant sensualism) that the original has lost his power to scandalize, surprise, or even interest us. I think, though, that this answer rests on an irreparably flawed premise.

The reality of the matter is quite the opposite: Juan is not familiar to us at all today, and the reason our cultural imagination no longer has much room for him - -and would certainly be incapable of producing another figure like him - is that he, far more than the buoyantly eternal Quixote, is a figure fixed in a particular cultural moment. He is not timeless, but only epochal. He personifies a long but circumscribed historical episode, apart from whose ambiguities and energies he is unintelligible: that twilight interval stretching between the late Renaissance and contemporary secular modernity. Juan was the greatest immoralist of European literature precisely because he served as the negative image of the moral convictions and capacities of his time and place, the exemplary contradiction of an entire and coherent vision of the good, whose story magically combined a certain nostalgia for fading cultural certitudes with a certain cynicism toward them. So, when the values of his time disappeared, he dissolved with them.

In truth, if he could speak to us today as clearly as he did to earlier generations, it would not be in the amiable tones of someone familiar to us but in a distant, almost prophetic voice, full of ironic moral reproach. He would tell us not of ourselves - of either our virtues or our vices - not even satirically. Instead, he would remind us of a vanished magnificence, inseparable from a now largely abandoned conception of what it is to be human.

Unlike Don Quixote, who made his debut in a work of genuine literary genius, Don Juan has always somehow exceeded the occasion of his first appearance. In fact, we are not even sure when he really did first appear. Tirso de Molina (the nom de guerre of Gabriel Téllez, a monk in his day job) wrote most of his plays between 1605 and 1625; but he did not include El Burlador de Sevilla in any collection of his works, so we do not know when - or perhaps even if - he wrote it. More to the point, as entertaining as Tirso's play is, it is neither an extraordinary literary achievement nor even necessarily the most authoritative version of the tale. Its chief importance lies in its having initiated a theme that for three centuries of European letters seemed nearly inexhaustible, and for having established the canonical pattern of Juan's tale as it was told in most subsequent renderings up to the time of Mozart's Don Giovanni. In the end, then, "Juan as such" is an abstraction, derived from a positively oceanic literary history, of which any distillate is necessarily only very partial. He has no single, wholly solid form, but comes to us in a series of shifting translucencies.

Certain essential elements of the character are there from the very beginning, however, if only in an inchoate way, and endure throughout his literary career. The most important, and by far the most attractive (literarily speaking), is his proud impenitence. This in itself is odd. Tirso intended his protagonist as a cautionary example of the vicious and debased state to which unrestrained appetite reduces a soul. His Juan, far from being meant to engage our sympathy, is for the most part rather uninteresting: an ordinary profligate, cad, and sexual predator of noble extraction, with sufficient means to pursue his desires and without any discernible sign of a conscience to impede the pursuit. When he comes to a bad end, we are supposed to recognize it as divine justice and to concur with the verdict.

But that is not quite what happened. Inadvertently, Tirso endowed his character with a faint but invincible glamour. A man so recklessly devoted to his own passions that he can careen knowingly into the very embrace of hell, without wavering from the course his own character steers him on, is intrinsically interesting. However repellent we may find his deeds, we cannot help but feel a certain exhilaration at, and even envy of, his unconquerable exuberance. And this, more than anything else, accounts for the figure's profuse longevity in European letters. It was Juan's insane inflexibility of will that almost all later versions of the tale, even when they were not intended to do so, seemed to celebrate.

But, again, Tirso's play, as he wrote it, is essentially a morality drama. It begins late at night in the royal palace of Naples, where Juan has gone disguised as one Duke Octavio so that he can bed the duke's fiancee, the Duchess Isabela. She discovers the imposture too late to save her honor (such as it is), but before Juan can elude the guard; he does eventually escape, though, his true identity still undiscovered, and flees the city. Isabela, to save face, allows Octavio to bear the blame.

En route to Seville, Juan and his servant Catalinón ("coward") are shipwrecked but manage to swim to shore, where Juan promptly seduces, enjoys, and abandons the fisherman's daughter who comes to his aid. On reaching Seville, Juan finds that report of his Neapolitan adventure has reached the court of Castile, as has Duke Octavio, but fortunately the duke still does not know who cuckolded him. The king, however, guesses easily and commands Juan to marry Isabela - whom he has summoned from Naples - and grants the duke the hand of a certain Doña Ana as a consolation. But Ana is in love with a certain marquis, and Juan, knowing this, disguises himself as her beloved and attempts a nocturnal assault on her virtue, of the sort that had worked so well with Isabela. Ana is not fooled, however, and calls for help. When her father Don Gonzalo, commander of the Order of CaItrava, comes to her rescue, Juan kills the old man and flees. The marquis is arraigned for the murder. Later, passing through the countryside, Juan happens upon a peasant wedding feast, seduces the new bride with promises of marriage, deflowers her, and then slips away back to Seville.

There, however, forces are gathering against him: Isabela, Octavio, the fisherman's daughter, the marquis, the peasant bride, and even Juan's own father, Don Diego. Meeting Juan in a church, Catalinón warns his master of the danger, but Juan is unimpressed. Then, in a side chapel, he comes upon a statue of the murdered commander and, mockingly pulling its beard, invites it to dinner. When, surprisingly, the statue appears for its meal, Juan betrays only momentary consternation and then plays host with all the panache one would expect of a true hidalgo. He even takes the statue's proffered hand and accepts its invitation to dine the following night in Don Gonzalo's chapel. Juan confesses to himself that the stone had burned his hand and that he had felt fear, but he quickly shrugs that off as something unmanly.

The next night, he goes to dinner as appointed, dragging Catalinón along; there, after the amenities have been observed (a dish of vipers, a cup of gall), the statue takes Juan again by the hand and draws him down to hell. Juan cries out in pain, and even asks to be shriven by a priest, but otherwise meets his end bravely. In the final scene, Don Diego's honor is restored, Octavio is reunited with Isabela, and the marquis is returned to Ana.

Anyone familiar with most of the notable versions of the tale from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries will recognize almost all the standard elements here, however much names and details may shift about in various tellings. Only a few additional features needed to be added by Tirso's successors. In the anonymous II convitato di pietra, from the 1650s, Juan's servant (now called Passarino) for the first time both produces the famous list of his master's conquests and cries out in despair for his wages when his master is taken to hell. In the various versions of the tale that entered the repertoire of the commedia dell'arte, the elevation of the story's comic aspects over the tragic became more pronounced. And the French playwright Dorimon penned a version in which Juan treats his own father so callously that the old man dies from emotional shock, which may be how the element of parricide entered the standard narrative.

The most original seventeenth-century treatment of the story is, without question, Molière 's Dom Juan ou Le Festin de pierre (1665), which, even if it is not a work of genius, is the work of a genius, and is the first treatment of Juan that is of genuine literary interest. Still, it has all the appearances of a work Molière might have concocted over a few winedrenched afternoons. It is written in prose, its structure is sprawlingly haphazard, and its abrupt finale is as nonchalant a piece of deus ex machina as any hack might have flung in the face of his audience. But the dialogue is hilarious, the characters have real dimensions, and the language is frequently splendid. Molière gave the world the French Juan: acerbic, coolly proud, skeptical, nonchalantly raffish, earnestly frivolous, naturally polygamous, a bad but not particularly abusive son, a duelist but not a murderer.